History of the Mosses

A history stretching back 12,000 years

Note: Links on this page take you to other pages within this website.

The Marches Mosses are the third-largest lowland raised bog in Britain. Until peat cutting and drainage began it covered a huge area some 2.5km wide and 8km long from Fenn’s Bank to Lyneal with large domes of peat rising up to 8 metres above the surrounding landscape. The Mosses encompass Fenn’s, Whixall, Bettisfield, Wem and Cadney Mosses. Over a third of this peatland has been lost due to human activities over the centuries.

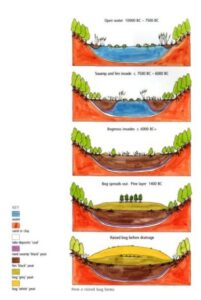

Peat formation

The peatland began to be formed during last glacial period, 12,000 years ago. Retreating ice sheets cut a low valley that runs southwest from Fenn’s Bank, forming a huge wetland area now known as the Meres and Mosses. Deep peat began to form along the edges of some of the meres as swamp plants – reeds and rushes – invaded, filling in the edges of the meres. Their remains allowed sedges and then alder and willow to take hold. This led to fen-peat building up higher than the nutrient-rich groundwater that fed the meres. Once that happened, Sphagnum moss, which needs nutrient-poor water to survive, began to colonise.

Sphagnum is the key plant in peat production. It holds rainwater and increases the acidic nature of the water. This pickled, water-logged habitat prevents most other plants from growing and, over centuries, forms peat. This in turn stores carbon that would otherwise be lost into the atmosphere.

Sphagnum magellanicum and S. papillosum Credit: Colin Hayes

The peat holds a record of the climate over millennia. As pollen grains fell into the peat and were pickled, they were preserved. This now provides a valuable record of climate changes since the peat was formed and helps scientists to better understand our current climate emergency.

Not just pollen has been preserved: the Marches Mosses also preserved three bog bodies that were found there in the late 1800s. Two of the bodies are thought to be from the Iron Age and one from the Early Bronze Age.

Peat Cutting

Local people first began to cut peat on the Marches Mosses in the later 1500s to use for fuel. From the second half of the 17th century, peat was cut commercially. Drains were cut to mark out sections allocated to householders, which caused the high peat dome to collapse.

Peat cutters’ pattens (overshoes to prevent sinking into the peat)

Peat cutting tools

Peat cutting expanded into large-scale exploitation of the Mosses in the early 1800s. This was facilitated by, first, the Llangollen Canal and, in 1863, a railway that was laid across part of Fenn’s Moss. These provided the means to get the peat to market. What is now known as Fenn’s Old Works was built in the 1930s to speed up production of bales of dried peat to send to market by rail. It’s located along the Mosses Trail and is a Scheduled Ancient Monument housing the only remaining National Heavy Oil Engine.

Commercial peat cutting firms operated from around 1850 until the Mosses were rescued in 1990 and mechanised peat cutting was stopped; hand cutting has been phased out since then.

The Mosses in Wartime

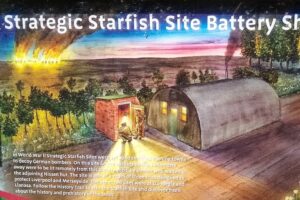

During World War I, the British military used part of the Mosses for artillery training. In World War II, part of Fenn’s Moss was turned into an incendiary bombing range for training by the RAF. Another part of the Mosses was used as a strategic Starfish decoy site. Large boxes of peat would be set on fire to make it look to enemy bombers that the site was Liverpool burning and so divert them. Visitors can learn more about the wartime works on the Mosses by following the History Trail from the Shed Yard car park.

Regeneration of the Mosses Begins – NNR Established and BogLIFE Project Underway

Since 1991, the Mosses have been a National Nature Reserve, with English and Welsh national nature bodies working to restore the peat. The site is now a Special Site of Scientific Interest (SSSI), a Special Areas of Conservation (SACs) and a Ramsar site as a wetland of international importance.

In 2016, the EU LIFE programme awarded Natural England a multi-million pound grant over five years to support the Marches Mosses BogLIFE project with the aim of restoring this valuable peatland. The partnership includes Natural Resources Wales and is also supported by the National Lottery Heritage Fund.

Also in 2016, Shropshire Wildlife Trust purchased the scrapyard on the south end of Fenn’s and Whixall Mosses with the help of Natural England and the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation. The scrapyard had been a pollution risk for some 60 years. Cleanup began in 2018 with over 100 truckloads of waste metals and hazardous materials and around 50,000 tyres being removed from the site. Contaminated ground at the site has been covered with turf and the area has been left to develop into woodland.

The Trust also purchased the fields across the Llangollen Canal from the Mosses, now known at Sinker’s Fields. They’re named after Charles Sinker who was instrumental in drawing attention to the need to save the peatland. Here visitors can use the bird hide to see birds such as curlew and lapwing, which use both the fields and the Mosses for feeding and nesting.

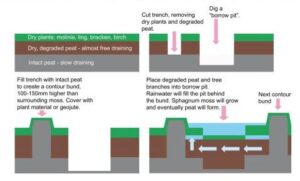

On the Mosses, the BogLIFE project support has meant that drains could be moved so they go around the edges of the Moss rather than through them This works to raise the water levels on the Moss, holding rainwater and “slowing the flow” to sites downstream. Invasive species such as birch, pine and bracken have been removed. The Natural England team have used a technique called cell bunding that captures the rainwater needed for Sphagnum moss growth that will, over time, create more peat.

Bio-diversity on the Mosses Increases

One of the results of the regeneration work is that the bio-diversity of the Mosses has increased. Curlews and lapwings can be seen overhead, as they can nest safely on the high ground of the bunds. Butterflies, moths, dragon- and damselflies have grown in numbers and the emblematic white-faced darter is back from the edge of extinction. Sundew, cranberries and other plants that depend on the acidic habitat of the Mosses can be spotted by keen walkers. All the while, more carbon is stored, acre for acre, than an equal area of woodland.

Curlews flying over Marches Mosses

Credit: Stephen Barlow

The work of the past 30 years has helped to restore damage done over centuries. The Mosses are a rare habitat with a wide range of wildlife, a huge carbon store and a wonderful place for people to enjoy an incredible, tranquil day out.