Tree removal on peatbogs

Note: Please be aware that links on this page take you to third party websites.

The Marches Mosses are precious peatlands for many reasons. Some of those reasons, like the carbon stored in the peat, aren’t visible but help us protect the Earth in the fight against climate change.

Other reasons are visible in the beauty and mystery that we can find on a walk on the Mosses, as we take in the peace and quiet, and share the peatland with the creatures and plants that can now make their home here.

You can learn more about the importance of restoring the Marches Mosses to its natural state in the questions and answers here.

Why are we removing trees? – To protect a rare 10,000 year old habitat

Fenn’s, Whixall and Bettisfield Mosses, a lowland raised bog, started life at the end of the last ice age approximately 10,000 years ago. Over this time the peat has built up as a result of millennia of the bog vegetation being annually ‘pickled’, giving rise to the special habitat we see today.

Bogs are characterised by being open landscapes covered with a specially adapted vegetation typically including species such as Sphagnum mosses, cotton grasses and sundews (JNCC). These plants thrive in the very wet and nutrient poor conditions found on a bog with Sphagnum acting as ‘keystone species’ actively encouraging water retention, high acidity and peat forming. This results in conditions that are unfavourable for trees to grow. So, in short, healthy bogs are open with a scattering of scrub and trees and wouldn’t naturally be woodland covered.

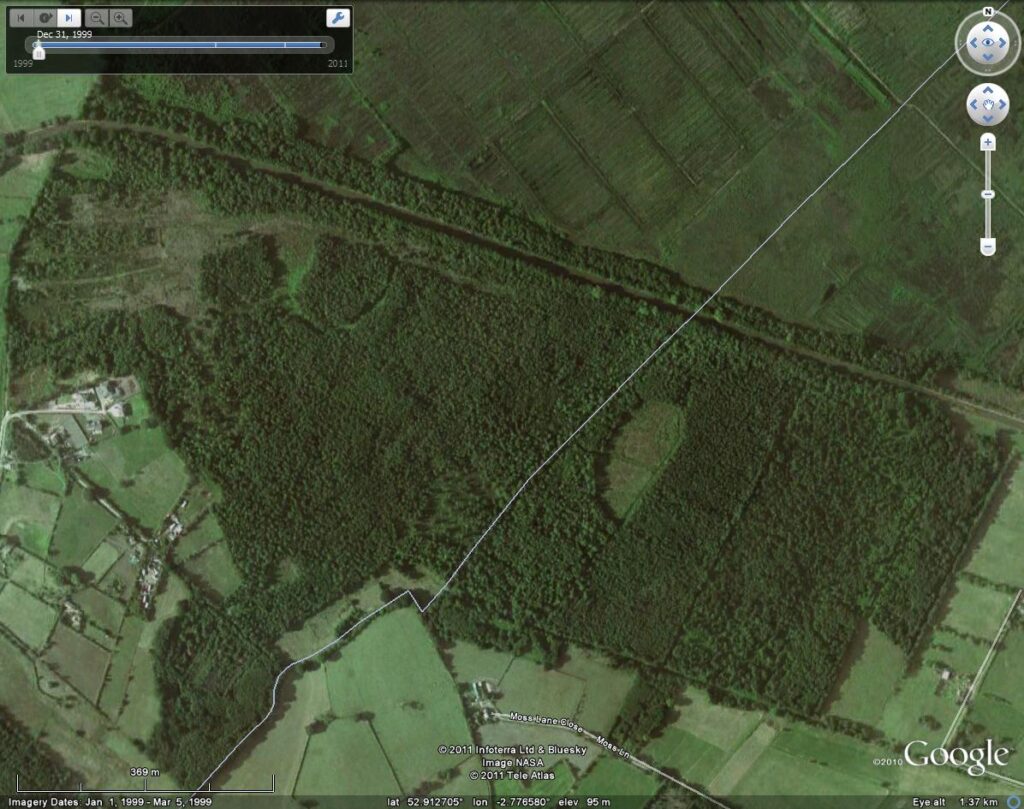

However, on the Mosses the large number of ditches and drains found across the bog has dried out the surface allowing trees to self-seed, establish and thrive. Many of the trees took hold after commercial peat cutting and the practice of regularly burning the Mosses stopped. On other parts of the bog, conifer plantations were planted relatively recently in the 1960’s. As such nearly all of the wooded areas on the Mosses are of relatively recent origins and none are ancient.

Whilst typically trees and woods are important in the countryside and to be encouraged, as explained above, in large numbers they are damaging to the delicate ecosystem of bogs. The deep roots and large leaf canopy of trees act like water ‘chimneys’, sucking large amounts of water out of the ground (up to 30% of the water table) which in turn makes the ground even drier. Gradually, once the trees become dominant, the bog vegetation and rare specialist species beneath that have been present for thousands of years decline and disappear.

Why are we removing trees? – An ecological priority

Nationally 94% of the lowland raised bogs have been lost (Climate Change Action Plan). Fortunately, Fenn’s and Whixall Mosses represents one of the best remaining examples, albeit quite damaged, of this rare habitat in the UK.

However the good news is that bogs are resilient and over the past 30 years there has been considerable progress in repairing past damage and restoring now flourishing areas of natural bog habitat. But, sadly, to repair some parts of the Mosses has meant management involving the selective removal of trees and wooded areas which have established over the past 30-60 years. This is undertaken to allow the peatland to be ‘bunded’ in order to restore squelchy, boggy conditions vital for the recovery of the bog plants and mosses.

What does an unhealthy bog mean for the specialist bog species that use and depend on them?

They become restricted to fragmented pockets of the healthy moss making local colonies vulnerable to destructive events such as wildfires as well as to the longer term effects of climate change, which may slowly shrink the size of their remaining strongholds. This can lead to their localised extinction if no action is taken to remedy such isolation. The species affected include the large heath butterfly, the white-faced darter, and curlew, many of which are also struggling nationally.

As Fenn’s, Whixall and Bettisfield NNR is the third-largest lowland bog in the UK, it is a nationally important stronghold for such species dependent on bog habitat. A key aim of the restoration work involving tree removal is to benefit such species by returning degraded areas of bog back to a healthy state which these species can once again inhabit.

Why are we removing trees? – From a climate change perspective.

While most of the debate around using natural habitats to draw down carbon from the atmosphere concerns planting trees and reforestation, Government policy increasingly acknowledges that a far better solution lies in restoring the peatlands that people have spent centuries draining and destroying. Each acre of bog at Fenn’s and Whixall Mosses contains 15 times the amount of carbon than the equivalent area of mature woodland.

Bogs, along with all other peatlands, are great at storing carbon. Carbon on a bog is stored in the peat soil and it is estimated that an enormous three million tonnes of carbon are locked in the peat at Fenn’s and Whixall Mosses.

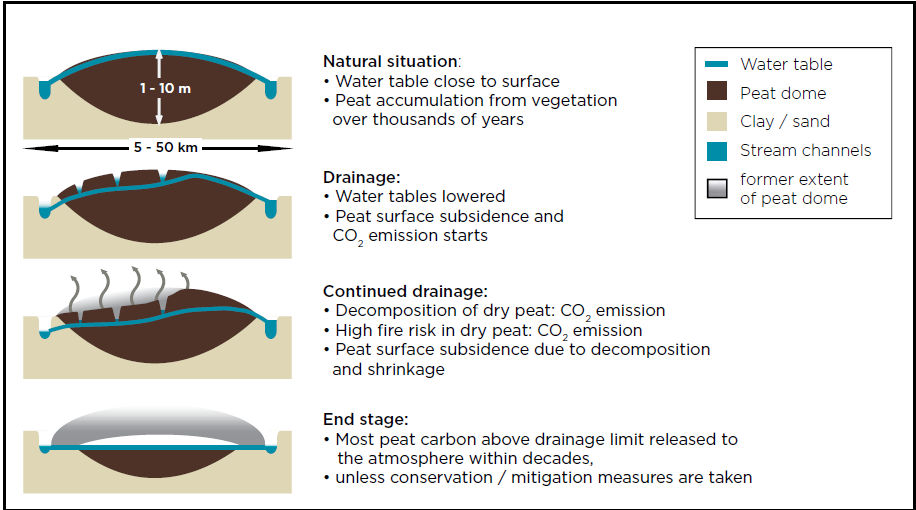

Peat is unusual in that very little of the organic matter (from dead plants/ leaf litter) is decomposed. Organic matter is full of carbon and when it decomposes that carbon is released into the atmosphere as carbon dioxide and methane. Decomposition is limited on a bog, meaning that carbon that would have been released is instead locked away. Decomposition is very slow on bogs because of their high water table; this keeps the peat constantly saturated with water, preventing air from reaching the organic matter which would speed up decomposition.

Due to this process, akin to ‘pickling’, peatlands form the largest natural terrestrial carbon store. Although they only cover 3% of the earth surface, peatlands store more carbon than all other vegetation types in the world combined and twice the carbon in all the world’s trees (IUCN).

Over the past 10,000 years, UK peatlands have sequestered around 5.5 billion tonnes of carbon from the atmosphere, gaining a further 370 million tonnes of CO2 to that total each year (IUCN), compared to the 150 million tonnes sequestered by our woodlands (JNCC).

On the other hand, degraded bogs where the peat is allowed to dry out release large amounts of carbon into the atmosphere – again. Astonishingly, degraded peatlands account for approximately 6% of human-caused carbon emissions globally (IUCN).

This adds an urgency to the restoration of as much of the degraded peat at Fenn’s and Whixall Mosses as possible. Without this change they will continue to release large quantities of carbon. Therefore, where trees are removed and the peat is rewetted, the goal is to stop carbon loss through peat wastage whilst encouraging the recovery of bog vegetation. This over time resets the active process of peat accumulation and carbon sequestration.

It seems counter-intuitive but, by restoring healthy bog habitat which sometimes involves the removal of trees that have encroached over the last 50 years, the important function of the mosses as, arguably, one of the region’s largest natural carbon sinks is being maximised, enabling it to play an important role in mitigating the impact of climate change.

How do we make sure that tree removal is undertaken with the least impact?

Decisions on tree removal have been carefully considered and planned. Each area has been assessed by ecologists in the team looking at both the existing species records for an area and the potential of an area to be restored as bog habitat. The latter is informed by peat depth survey information to assess if the water retention technique called peat bunding is suitable to be used.

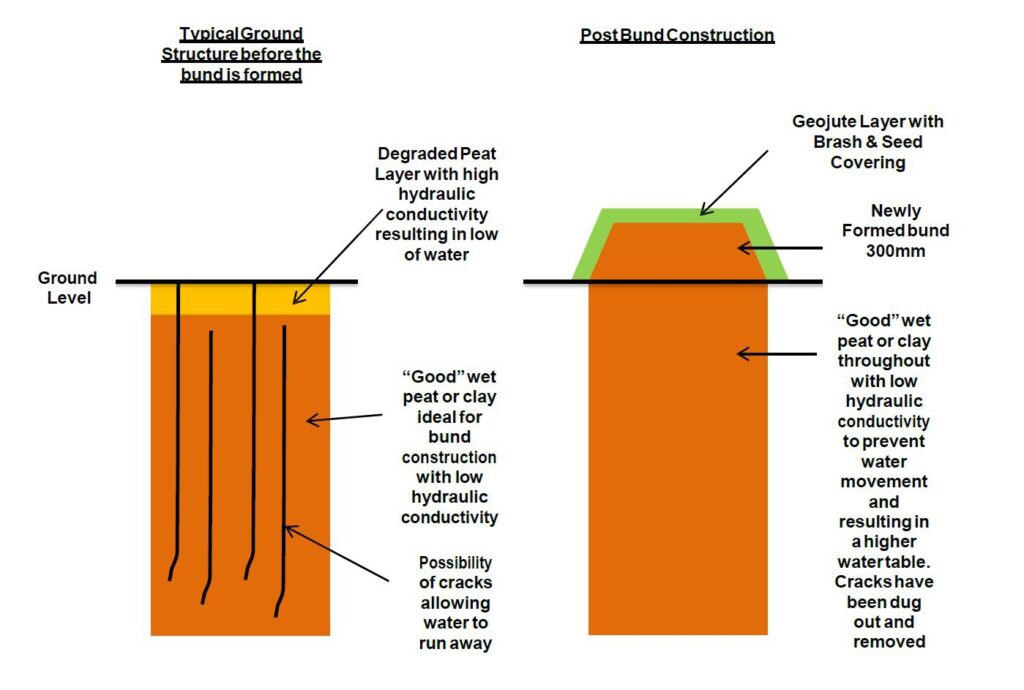

A brief explanation of bunding. The peat underground in many places will still be saturated with water; this peat still holds its water instead of allowing it to drain away like the degraded top peat does. Bunding uses this deeper peat to make a 30cm tall bund that will hold back rainwater in a cell. This allows the degraded peat within the cell to rewet and ‘re-pickle’. The process of digging down to the ‘good’ peat also breaks up any underground water drainage channels meaning that water is stopped from draining away both above and below ground

In selected edge locations with shallow peat, the bunding will encourage development of wet woodland. This rare habitat would naturally have occurred at the edge of the bog in the past. Some tree clearance will still be undertaken here in order to allow the diggers access for bund creation.

Where appropriate, a margin of trees is retained around the felling areas to help provide a weather and landscape buffer and to serve as a wildlife link between retained wooded areas. Many of the drier sandy areas on the edge nature reserve will also be left to regenerate to scrub and woodland over-time.

What does the future hold for areas where trees have been removed?

Once the trees have been removed and the bunds are in place, this should allow the area to develop into a habitat more suitable to the more vulnerable locally occurring species. This may need ongoing scrub management over future years to come to give the slower growing bog plants a chance to establish.

Bettisfield Moss is an example of formerly wooded area successfully restored. The open area you see today was formerly a conifer plantation. The trees were harvested around 20 years ago and the bunding works have taken place over the past 3 years.

Today it is covered by flourishing high quality bog vegetation and home to some of the rarest species on the nature reserve.

Have trees removed been replaced?

Yes, many of the non-peat areas on the nature reserve, e.g. sandy ground, that are currently open will be managed as deciduous woodland. The trees will be established through both natural regeneration as well as selective tree planting.

Wet woodland areas will also be allowed to naturally regenerate although some selective scrub removal will continue to be undertaken to prevent future trees roots damaging the peat bunds which manage the water levels.

Useful Links:

Meres and Mosses- FAQ’s: https://themeresandmosses.co.uk/faqs/

JNCC Description of Lowland Raised Bogs: https://data.jncc.gov.uk/data/aadfff3d-9a67-467a-ac65-45285e123607/UKBAP-BAPHabitats-31-LowlandRaisedBog.pdf

Biodiversity Action Plan. Lowland Raised Bog: https://www.nature.scot/sites/default/files/2018-01/UK%20Biodiversity%20Action%20Plan%20-%20Priority%20Habitat%20-%20Lowland%20Raised%20Bog.pdf

Climate Change Adaption Manual 2020: http://publications.naturalengland.org.uk/publication/5679197848862720

Peatlands and Climate Change: https://www.iucn.org/resources/issues-briefs/peatlands-and-climate-change

Sphagnum Description: https://www.wildlifetrusts.org/wildlife-explorer/mosses-and-liverworts/sphagnum-moss

Ancient Woodland Information: https://www.woodlandtrust.org.uk/trees-woods-and-wildlife/habitats/ancient-woodland/

Wet Woodland Information: https://www.woodlandtrust.org.uk/trees-woods-and-wildlife/habitats/wet-woodland/