Starling flocks attracting the crowds

December 2, 2019

Note: Please be aware that links on this page take you to a third-party website.

The cold weather and clear skies have made viewing the starling murmuration at Whixall a must-see over the last few days. With the forecast looking good for the next week, more people are likely to be visiting the Whixall area than usual for this time of the year. Over 60,000 starlings are thought to be roosting along the willow strip opposite the scrapyard. The sight is made all the more spectacular by the recent incredible winter sunsets.

Where is the best place to view the murmuration?

The starlings gather in the skies around the old scrapyard site on the edge of Whixall Moss. They can be viewed from the lane alongside Shropshire Wildlife Trust’s recently acquired fields at Morris’s Bridge and from the canal side anywhere between Morris’s Bridge and Roving Bridge. Click here to see a map

Where is the best place to park?

Although there are a couple of laybys along the lane towards the canal, we recommend parking on the official nature reserve car park, located just on the other side of Morris’s Bridge. Parking spaces are limited, so please park sensibly to allow the maximum number of people to use the car park.

What time does the murmuration start?

The starling flocks begin to gather at sunset. Arrive for 4pm to ensure that you don’t miss it.

Why do murmurations happen?

Starlings live in a complex societal system which we still don’t fully understand, but there are a number of reasons for them gathering in such spectacular fashion. During extreme cold, multiple starling flocks gather and roost together for combined body warmth.

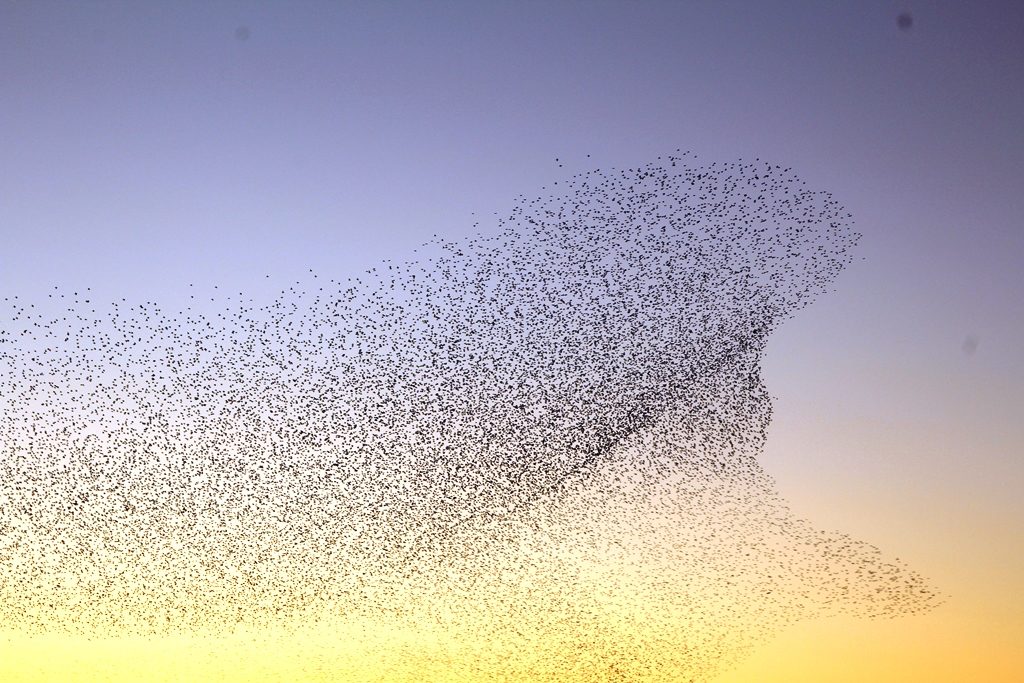

But the key reason for so many birds flying in unison is all about safety in numbers. Starlings often fall prey to sparrowhawks, peregrine falcons and hobbies, all of which can catch them mid-flight. The best way to avoid being caught is to lose yourself in a huge crowd. Predators struggle to pick out individual birds when there are so many flying in close proximity. Studies have shown that starlings are able to move quickly and change direction as a group by reacting to the movement of the birds immediately surrounding them. Scale that up to tens of thousands of birds and the result is a mesmerizing spectacle; a shape-changing dark mass in the sky. Once the flock has determined that their chosen roost site is safe, they begin to pour into trees and bushes from the sky. It is estimated that there are around 60,000 birds in the flock at Whixall.

Below are some videos and images of the murmuration at Whixall. Visit the Shropshire Wildlife Trust website to read more about starlings, nature reserves in Shropshire and how you can help to protect them.