We Bet You Haven’t Thought About Drains on the Mosses

March 2, 2021

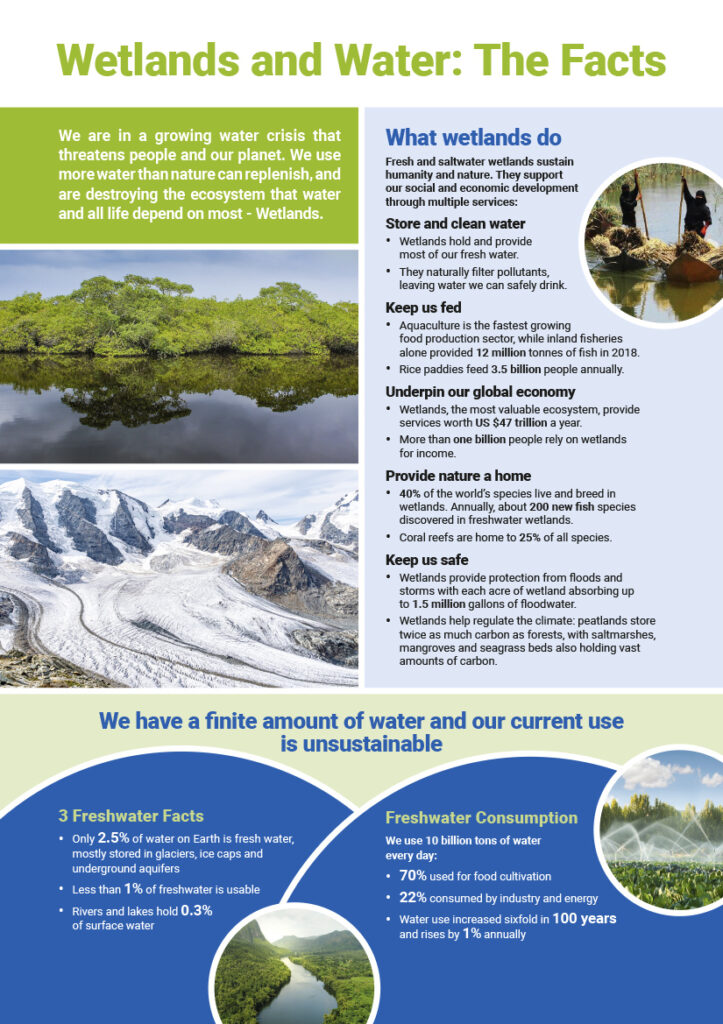

If you read about the Marches Mosses here on this website, or follow the Mosses on Twitter, you’ll know that peat bogs are an important feature of the Earth’s environment. They store carbon, helping to fight the climate crisis; they are a valuable habitat for creatures and plants that make their homes on them. In fact, many bog plants and animals depend completely on the acidic nature of peatlands to thrive. Healthy peatbogs also store vast amounts of water which helps to slow the flow of water off the Mosses, helping to reduce flooding downstream.

The Mosses have been changed by human activities over the centuries. Peatcutting changed them dramatically, but huge swathes of bog were also drained to create new fertile land for farming. And drains have had a significant influence on the areas of moss that remain. Yep, we said drains.

Healthy peat depends on rainwater – and only rainfall and moisture in the air – to keep the peat wet and provide water and the low levels of nutrients that plants like Sphagnum mosses need to grow.

What healthy peat doesn’t need, or want, is the nutrient-rich water that drains off of mineral soil – the soil that forests, grasslands, farms and our back gardens depend on. That’s where the drains come in.

But first, a bit of history before we dive into the solutions.

The History

Damaged peat is very likely to be dried out. Peat dries out because it’s been drained, allowing the water to run off the bog. The the mosses that make up the Marches Mosses were drained for centuries, in order to dry out the peat so it could be cut for fuel and agricultural uses.

Drainage certainly goes back to the first Inclosures in the early 1700s. The Inclosure of 1823 defined five principal public drains to carry water off Whixall Moss. The drains were the responsibility of the Lord of the Manor and had names as uninteresting as Main Drain and as unusual as Chatty Bottoms.

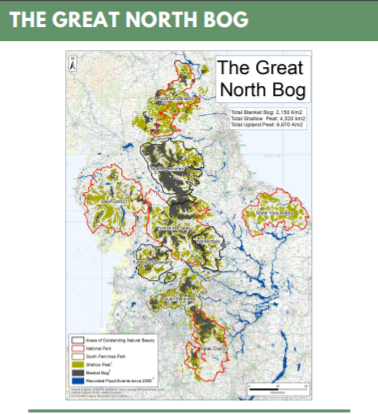

The drainage led to the collapse of much of the raised dome of peat on the Marches Mosses. For instance, the northern dome of Wem Moss was damaged by the creation of the Border Drain; otherwise, the dome would have continued into Cadney Moss. The southern dome was damaged by drainage as well. Aerial images of the site show the extent of drains across Fenn’s, Whixall and Bettisfield Mosses.

Adding to the woes, the drains allowed nutrient-rich water from the surrounding farms, houses and villages to drain onto the Moss. This led to the growth of invasive species – bracken, scrubby birch and purple moor grass among others – that draw water up from the bog, further drying the peat. Neighbouring Wem Moss, managed by Shropshire Wildlife Trust, was completely drained by the 1980s and the whole peat layer became hidden under a blanket of those dominant, invasive plant species. If left unmanaged, Wem Moss would no longer be a Moss at all – just a thick jungle of birch, surrounded by willow forests; both of which are unsuitable for bog specialist wildlife.

The Solution

The solution has been underway on the Mosses since the 1990s when they were protected as a National Nature Reserve. Work involves damming up the small drains to keep rainwater on the Mosses and installing bunding on parts of the bog to re-wet the peat and make it ideal for generating moss growth. Some of the larger drains have also been re-configured to prevent nutrient-rich water from entering the Mosses. This changes the ecosystem, making it ideal for the unwanted plants to start developing and dominating bog plants.

When you’re out walking on the Mosses, you might see work being done to reconfigure drains – there’s work going on now to re-direct the Bronington Manor drain that runs across the Mosses, around the northern area of the dismantled railway path.

The Benefits

One of the benefits of restoring the peat on the Mosses to health is cleaner water flowing into the rivers downstream. Water that does flow off the bog is rainwater that’s been slowly filtered through the peat, helping to keep the rivers that much cleaner, meaning less work is needed to provide fresh water to people in the area. In fact, there are two watersheds from the Mosses – one that flows north to join the River Dee as it flows toward Chester, and the other, south to the River Roden which eventually joins the River Severn.

In summary, drains are an important part of the life of a bog. They keep the “wrong” water off the Mosses and keep the “right” water on to keep the peat wet, allowing it to store more carbon, while slowing the flow of rainwater off the Mosses, helping to prevent flooding downstream while filtering the water that eventually joins the Dee and the Severn.