Rescuing Our Peatland: Everything you need to know about peat restoration.

August 20, 2021

Note: This post has links to external websites.

Special thanks to Ellie Williams, Marches Mosses BogLIFE Assistant Project Officer, for this article.

The Marches Mosses is a special landscape that we are working to restore and protect for future generations. Peatlands such as Fenn’s, Whixall and Bettisfield Mosses play an important role in the fight against climate change due to their amazing carbon storage abilities.

This article has everything you need to on why the restoration and ‘re-wetting’ of the peat is so important, along with how we do this and what we hope to achieve.

What is peat?

Peat is a type of soil that has a high percentage of partially decomposed vegetation matter, created in the wet conditions found in bogs. It is very dark brown in colour and has a ‘squelchy’ texture. Peat is also very good at holding onto water, much like a sponge; this is why it is squelchy.

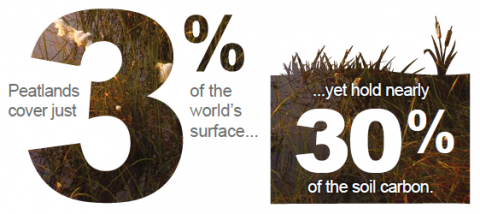

Vegetation, as with all living things, is full of carbon. In other habitats this carbon decomposes which releases that carbon back into the atmosphere. However, decomposition is very slow on a bog so this carbon isn’t released into the atmosphere. Instead it is stored underground for potentially thousands of years.

Why is peat important?

The high carbon content of peat is what makes peatlands so important in the fight against climate change. Fenn’s and Whixall Mosses have been accumulating peat since the end of the last Ice Age over 10,000 years ago, sequestering around 3 million tonnes of carbon!

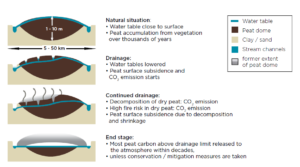

The concerning part of this amazing ability is that peatlands will only store carbon if they are healthy and full of water. When a peatland is drained and the water table drops, the peat that was saturated dries out. Once the air has access to the peat it will cause the peat to decompose. This releases the carbon it has been storing away for thousands of years back into the atmosphere.

This is a major problem, so much so that damaged, unhealthy peatlands make up 6% of all human-caused CO2 released into the atmosphere every year.

This is why restoration is so important: it will limit the carbon being released and allow the bog to store the carbon instead. Fenn’s Whixall and Bettisfield Mosses is the third-largest raised peat bog in the UK so its restoration is of national and international importance.

Fenn’s and Whixall Moss – A damaged landscape

As is the case with the majority of bogs in the UK, Fenn’s and Whixall Moss was historically cut for peat both on a localised and commercial scale. This, along with other past uses, has created a very damaged peatland. Peat has a wide range of uses for combustion, horticulture and was even used as a building material. To extract the peat, a vast network of ditches were cut across the Moss to allow peat cutting to take place.

Peat cutting stopped in 1990 when, due to a local outcry, the site became the National Nature Reserve (NNR) it is today. However, the ditches that were created in the industrial part of its life still remain. Over the past 30 years the NNR staff have dammed up countless ditches at regular intervals to reduce the flow of water off the site, but the bog is still far drier than it should be.

On a pristine, uncut bog the water table shouldn’t drop more than 10cm below the surface. At Fenn’s and Whixall the water table can drop far lower to over 50cm, which is only made more extreme in dry summers. What this means is the top surface of the peat is drying out, allowing it to decompose and release carbon back into the atmosphere.

How do we restore the peat?

There are three main techniques used on bogs to help retain water:

Dams: Damming uses nearby good peat to block ditches. ‘Good peat’ is the undisturbed peat that has stayed saturated so is squelchy and dark in colour. In damaged bogs you typically have to dig down to find it Good peat does not allow water to pass through it, so filling and compacting good peat in a ditch at regular intervals reduces the amount of water flowing off site. The water backs up behind the dams, re-wetting the peat behind up to the dam’s height.

Photo: Peat dam in East Ayrshire Credit: Coalfield Environment Incentive

Plastic Piling: Corrugated plastic sheets are pushed into the ground to stop water. These are used for ditches in shallow peat, slopes and at the edge of bogs to make the water build up behind them, creating a re-wetted area.

Photo: Plastic piling being used to block a ditch. Credit: Peatland Action

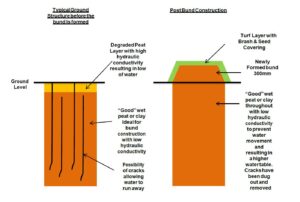

Bunding: This is a relatively new technique where good peat is used to make small embankments across the open Moss. These embankments are approximately 30cm high. The good peat is dug out to roughly 1m deep and gently compacted down to make a berm. The peat is then covered with vegetation to protect it from drying out and potential erosion from rainfall.

Photo: Bunding on Fenn’s and Whixall Moss Credit: Fenn’s and Whixall NNR Team

This process breaks any underground water channels and creates an impermeable barrier underground and up to the top of the peat embankment. Any rain that falls in the area can’t drain away, allowing the peat to re-wet. These embankments are typically made in rectangular shapes connected in a honeycomb-like pattern.

Since 2017, the team at Fenn’s & Whixall have been planning and facilitating the bunding works carried out by skilled contractors around the perimeter of the Moss. This will hold more water on the bog and slow outflow from the centre of the Moss as it has to travel through the bunded system before going downstream. Bunding the perimeter while damming the ditches in the centre will improve large areas of the bog due to the expected increased water table on the bog and slowing the flow leaving the site.

We are not the first to use bunding; this technique has also been used to help other reserves such as Humberhead NNR, Bolton Fell Moss (Cumbria), and Cors Caron NNR (Ceredigion).

How are bunds made? Below is a diagram of before and after bund construction.

How do we limit negative impacts?

A variety of bird species choose to nest on the reserve, from your bird feeder regulars such as the great tit to the nationally in decline curlew. To limit disturbance to any nesting birds, the bunding works are done over the winter, starting in August when nesting has finished and working until the end of February. On occasion the works will extend later into spring but only in areas where the land has a low nesting potential and nesting bird surveys have come back clear of prospecting and nesting birds.

We are lucky at Fenn’s and Whixall to have a population of adders. This native snake is in sharp decline nationally. Adders look for hibernation sites in dry high lumps of peat with sheltered hiding spots and a good view of the sun so they can warm up in the spring. In addition, the bunds themselves are used by wildlife, with adders seen to be using them to navigate around the site. When planning the routes for the bunding works, appropriate hibernation locations are avoided as much as possible and any known hibernation lumps are given a wide berth.

An unexpected friend

Throughout the planning and progression of the bunding works, we try to ensure that the diggers avoid wildlife as much as possible. So we did not expect the wildlife to come to them!

Last winter a local buzzard took a liking to the excavators and was an almost daily visitor, staying very close throughout the day. We saw it hopping over the newly-made bunds and even perching on the diggers themselves.

This isn’t their first feathered friend either – a resident kestrel also followed the bunding works closely in previous winters.

Although we cannot know for certain why, we think they take advantage of the insects, grubs and worms unearthed when the underground peat is exposed for bunding, much like the way robins will eagerly watch a gardener but on a larger scale.

Photo credits: C. Holgate

A brighter (and wetter) future

From a climate change perspective, bunding will allow the bog to have a higher average water table because the water can’t drain away as it used to due to all of the drainage ditches. This will instead saturate the peat and halt decomposition, allowing the peat to be a carbon store instead of releasing CO2 into the atmosphere as dried peat does.

Climate change is also altering our weather; the current projections from the Met Office show that the UK is likely to experience warmer, wetter winters with hotter, drier summers along with an increase in the frequency and intensity of extreme weather. The bunds will help the bog to store more rainwater in storm events, as well as hold that water for far longer to help the bog in future drought conditions.

This is because the more rainwater that we can keep on the Moss, the less will be flowing off the reserve and downstream. This creates a win-win situation as the reserve gets to keep the rainwater it desperately needs and the downstream waterways have a lower volume of water to cope with, making them less likely to overflow. Any runoff from the reserve should also be delayed, allowing more time for the initial surge of water from surrounding farmland to subside.

Although we’re sure the buzzard will miss the diggers, in the long term the bunds will increase the water table and help promote our bog specialist plants. This helps them to compete against more aggressive species such as purple moor grass and birch which prefer the lower, fluctuating water table. These bog specialists include species of Sphagnum, cotton grasses and sundew, for example. This in turn helps other bog rarities such as the large heath butterfly that rely on these bog plants for their life cycle. Furthermore, with more pools that remain wet throughout the year, our dragonflies will also benefit, along with wading birds and hobbies which feed on the dragonflies.

Peat Restoration in a Nutshell

To summarise, peatlands are globally important in the fight against climate change due to their ability, when in good condition, to take carbon from the atmosphere and hold that carbon in the peat for potentially thousands of years. However, peatlands are drained that carbon is instead released into the atmosphere.

Fenn’s, Whixall and Bettisfield Mosses is the third-largest lowland bog in the UK and is a degraded peatland. The BogLIFE project is funding a five-year restoration programme which aims to re-wet the peat and in turn make the Mosses a carbon store, and no longer a source.

The main technique being used to do this is called bunding. This process uses specialist diggers to dig down to the good, water impermeable peat underneath which is then used to make small embankments in a series of cells in a honeycomb style to hold the rainwater on site.

The result is that any rainwater falling on these areas should stay in the bunded cells instead of flowing into the ditch system. With more water held on site the damaged peat should re-wet. This will prevent more peat from decomposing and releasing carbon dioxide back into the atmosphere; allowing the site to store more carbon.

Additional benefits to re-wetting the peat is that it will improve conditions for the rare, bog specialist species such as the sundew and large heath butterfly that rely on the Mosses, many of which are struggling nationally. More pools on the Moss are great for our dragonflies and wading birds. Then finally, as the Mosses can then hold more water on the site it will further reduce any contributions to downstream flooding, as there will be a reduced and slower flow off the Mosses into the downstream ditches.

This means peat restoration works benefit national carbon emissions, wildlife and the local drainage network now and into the future.

Useful Links

National Trust Article on Peatlands: https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/features/whats-so-special-about-peat

Met Office Climate Change Summary: https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/binaries/content/assets/metofficegovuk/pdf/research/ukcp/ukcp-headline-findings-v2.pdf

Peatland description and habitat types: https://www2.le.ac.uk/departments/geography/research/projects/tropical-peatland/what-are-peatlands

Raised Bog Description: https://www.wildlifetrusts.org/habitats/wetlands/raised-bog