Why We Need to Restore Precious Peatland Habitats

February 10, 2021

Note: Please be aware that links on this page take you to third party websites.

The Wildlife Trusts, of which Shropshire Wildlife Trust is a member, issued a press release today about the need to protect and restore UK peatlands. You can read the press release here. Some interesting facts relating to this help to draw a clear picture of the need to restore precious peatlands habitat, as the BogLIFE project at the Marches Mosses in Wales and Shropshire is doing:

Peatlands cover as much of the UK as forests, but store three times as much carbon.

- Whilst peatlands may bring to mind the upland peat bogs of northern England, Scotland and Ireland, there are important peatlands across other parts of the country too, from Dartmoor in the west country, to the low-lying fens of Eastern England, to the lowland raised domes of the Marches Mosses.

- In fact, altogether, peat soils cover about a third of the UK, with deeper soils – peatlands like the Marches Mosses – covering about 12%.

- When in their natural wet state, peatlands hold carbon in soils that have built up over thousands of years. When peatlands dry out, the carbon combines with oxygen to form CO2. Scientists have estimated that if all the carbon held in the world’s peat soils were released, it would raise CO2 levels by 75%, with catastrophic consequences for global climate. This emphasises the need to protect and restore the peatlands.

- The UK’s peatland soils store around 3.2 billion tonnes of carbon. Compare that to the roughly 1 billion tonnes of carbon that are locked up in UK woodlands, mostly in the soils; these cover 3.21 million hectares or about 13% of the UK. Thus, peatland stores three times the amount of carbon as forests in the UK.

Peatland provides natural flood protection

Peat soils and vegetation hold water well and provide natural flood protection by catching downpours. Nearly three quarters of the UK’s water supplies come from peatland catchments; when those catchments are well-managed, water companies spend less treating that water to make it drinkable. When peat bogs are cut, lots of humic acids – decayed leaf litter, basically – are released and the water leaving the Moss is dark brown, whereas water off restored peat areas is clearer.

Peatlands provide a respite for people and wildlife

Gatekeeper butterfly

Curlew

Sundew

In addition to the contributions of peatland to the fight against climate change, they also provide benefits for people and wildlife. People can enjoy walks in the quite, open expanse of the peatland – a healthy change from busy, urban life. Creatures and plants, many of which can only thrive in the acidic nature of the peat, have made peatbogs their home.

There’s an archeological benefit, too: peatland provides an irreplaceable chronological history of the environment over the 10,000 years or more that they developed, with information captured in layer upon layer of peat.

Plans to restore additional peatland to store carbon

- The Committee on Climate Change (CCC) is an independent, statutory body established under the Climate Change Act 2008 to provide independent advice on setting and meeting carbon budgets and preparing for climate change. Their Sixth Carbon Budget, published in December 2020 and entitled “Agriculture and land use, land use change and forestry” describes the need to restore peatlands:

- The roughly three million hectares of peat soil in the UK breaks down this way:

- Around 25% is currently in natural condition (wet and well-managed bogs and fens);

- 40% is degraded upland grassland;

- 15% is lowland grassland or cropland;

- 15% is under forestry;

- 5% has been extracted.

- To reach net zero carbon emissions, the CCC has recommended:

- All upland peatland be restored by 2045 (1.2million ha).

- Between 25% and 50% of lowland peatlands, which is equal to 100,000 -200,000ha, are restored by 2050.

- The remainder needs to be brought into sustainable management.

- The UK BEIS Emissions Inventory for Peatlands project suggest less than 110,000ha has so far been restored out of the more than 2million ha of peatland that is in a damaged state. (Table 3.4 in the BEIS document.)

- The Government has committed £50m through the Nature for Climate Fund to restore 35,000 hectares of England’s peatland by 2025.

Examples of other peatland restoration projects

Examples of peatland restoration in the UK, in addition to the BogLIFE project on the Marches Mosses, include:

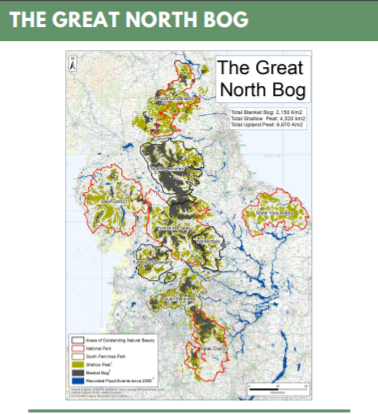

- The Great North Bog: Peatland restoration programmes in the north of England have developed a vision that stretches across 7,000 square kilometres of upland peat in the Protected Landscapes of northern England, which currently store 400 million tonnes of carbon. Damaged peat in the Great North Bog releases 3.7 million tonnes of carbon annually. The programme aims to develop a working partnership to deliver a 20-year funding, restoration and conservation plan to make a significant contribution to the UK’s climate and carbon sequestration target. You can read more here.

- Of Lincolnshire’s original 100,000 hectares of wild wet fenland, only 55 hectares now remain – a loss of over 99.99%. This loss is responsible for the decline and extinction of much of the flora and fauna that depend upon these diverse wetland habitats. The Bourne North Fen is Lincolnshire Wildlife Trust’s project to restore 50 ha of fenland.

- The Wildlife Trust for Bedfordshire, Cambridgeshire & Northamptonshire is working with farmers in the Great Fen on field-scale trials of ‘wet farming. These test innovative new crops for food, healthcare and industry that may prove very profitable for farmers. This also keeps the peat soils wet, preventing their degradation, and scientists are monitoring the carbon benefits of the project. Plans are underway to grow 150,000 Sphagnum plants which can be harvested to make alternatives to peat compost, helping to bring an end to extraction from bogs for this use.